🇪🇸 Leer en español

📃 Read in Chapters

On Naur’s Documentation Pessimism

In 1985, Peter Naur argued that programming is theory-building, and that theory cannot be fully captured in documentation. But his pessimism is narrower than supposed. It applies to technical documentation of artifacts, not documentation as a human endeavor. AI doesn’t “solve” the problem—but it creates conditions where theory transmission becomes more likely.

In 1985, computer scientist Peter Naur published “Programming as Theory Building”—a short, influential essay arguing that programming is fundamentally about building mental models, not producing code. The programmer’s theory of how real-world problems map to software is the essential product; code and documentation are secondary artifacts. Crucially, Naur claimed this theory cannot be fully captured in documentation, because it involves tacit knowledge that defies formalization. (See our summary or the original paper.)

But Naur’s pessimism targets technical documentation—specs, code, design docs—not all written communication. The Renaissance proves documents can transmit theory when written to do so.

AI collaboration doesn’t solve the documentation problem by reducing labor (that misreads Naur’s epistemological argument). But it creates novel conditions: forced articulation, preserved dialogue, lower-friction iteration. These make theory transmission more likely, even if never complete.

Chapters

- Preface — Who wrote this, and why the strawman caveat matters

- Naur’s Actual Argument — Epistemological, not economic

- The Strawman to Avoid — What AI doesn’t solve

- The Scope of Pessimism — Artifact-focused docs only

- Evidence from Cultural Transmission — The Renaissance argument

- Why Technical Documentation Fails — Cockburn’s analysis

- Forced Articulation — AI as interlocutor

- Dialogue Preservation — Capturing the problem-solving process

- What Remains Unsolved — Tacit knowledge persists

- Toward Theory-Resilient Documentation — Practical recommendations

- Conclusion — Synthesis

References

- Alexander, C. (1977). A Pattern Language. Oxford University Press.

- Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press.

- Cockburn, A. (2006). Agile Software Development (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley.

- Kernighan, B. W., & Plauger, P. J. (1976). Software Tools. Addison-Wesley.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Naur, P. (1985). Programming as Theory Building. Microprocessing and Microprogramming, 15.

- Polanyi, M. (1973). Personal Knowledge. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Ryle, G. (1949). The Concept of Mind. Hutchinson.

Preface

Author: Ricardo Rocha Date: 2025-12-24 Status: Working paper

This paper articulates a refined understanding of Peter Naur’s “Programming as Theory Building” (1985), arguing that his famous pessimism about documentation is narrower than commonly supposed—and that human-AI collaboration creates conditions for theory transmission that Naur could not have anticipated.

The Strawman Caveat

Before proceeding, an act of intellectual honesty.

The original thesis for this paper was: AI collaboration makes theory preservation possible because it reduces the labor costs that made comprehensive documentation impractical.

This is wrong. It misreads Naur’s argument. His pessimism is epistemological, not economic. He claims certain knowledge cannot in principle be articulated—not that we lack time to articulate it.

We include this caveat explicitly because others will arrive with the same intuition. The strawman is attractive. Rejecting it sharpens what AI collaboration actually changes—and what it doesn’t.

I. Naur’s Actual Argument

Peter Naur’s “Programming as Theory Building” (1985) proposes that programming should be understood not as the production of program texts but as the building of theory in the minds of programmers.

The Three Capacities

This theory, drawing on Gilbert Ryle’s epistemology (1949), encompasses:

- Explanatory capacity — The programmer can explain how the solution relates to the world it addresses

- Justificatory capacity — The programmer can explain why each part is what it is

- Modificatory capacity — The programmer can respond constructively to demands for change

The third capacity is crucial. Anyone can read code and understand what it does. Only someone with the theory can know how to change it correctly when circumstances shift.

The Central Claim

Naur’s central claim is that theory “could not conceivably be expressed” in documentation because it involves tacit knowledge that defies formalization:

“The dependence of a theory on a grasp of certain kinds of similarity between situations and events of the real world gives the reason why the knowledge held by someone who has the theory could not, in principle, be expressed in terms of rules. In fact, the similarities in question are not, and cannot be, expressed in terms of criteria, no more than the similarities of many other kinds of objects, such as human faces, tunes, or tastes of wine, can be thus expressed.”

This is an epistemological claim, not an economic one. Naur is not saying “we lack time to document properly.” He is saying that theory involves recognition of similarities that are, in principle, beyond explicit formulation.

The distinction matters. If the problem were time, more effort would solve it. If the problem is epistemological, no amount of effort helps.

II. The Strawman to Avoid

Before proceeding, we must explicitly reject an attractive but flawed argument.

The Strawman

Naur’s pessimism about documentation was valid for his time because keeping theory and code synchronized through documentation was a gargantuan undertaking that only humans could perform. Humans lack the time, energy, and cognitive capacity to maintain such documentation effectively. AI collaboration changes this equation by reducing labor costs, making theory preservation possible in ways Naur couldn’t have envisioned.

This argument misreads Naur. His pessimism is not rooted in labor costs but in the nature of tacit knowledge. If the problem were merely that documentation is laborious, then more effort (or AI assistance) would solve it. But Naur’s claim is stronger: certain knowledge cannot in principle be articulated, regardless of how much time or assistance one has.

The Impossibility Witnesses

Michael Polanyi, whom Naur cites, makes this vivid:

“It is pathetic to watch the endless efforts—equipped with microscopy and chemistry, with mathematics and electronics—to reproduce a single violin of the kind the half-literate Stradivarius turned out as a matter of routine more than 200 years ago.”

No amount of documentation labor could capture what Stradivarius knew tacitly.

Christopher Alexander reached the same conclusion in architecture. His Quality Without a Name—the property that makes spaces feel alive rather than dead—is immediately recognizable yet indefinable. Alexander spent years codifying patterns (A Pattern Language, 1977), producing 253 of them, yet acknowledged that following the patterns doesn’t produce the quality. As he wrote:

“There is a central quality which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building, or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named.”

The Convergence

Three domains—craft (Polanyi), architecture (Alexander), programming (Naur)—converge on the same epistemological wall. This is not coincidence but evidence of a structural limitation in formal systems.

Naur would likely respond to claims about AI: “AI is just another formal system; it cannot capture what humans themselves cannot articulate.”

We must not claim that AI “finally solves” the documentation problem. That would be to misunderstand what the problem is.

III. The Scope of Naur’s Pessimism

Having established what Naur actually argues, we can now observe that his pessimism has a specific scope.

What Naur Critiques

The documentation Naur critiques consists of:

- Program texts

- Annotated code

- Specifications

- Design documents

- User documentation

His Case 1 is illustrative: Group B received “full documentation, including annotated program texts and much additional written design discussion” from Group A, yet repeatedly proposed modifications that “made no use of the facilities that were not only inherent in the structure of the existing compiler but were discussed at length in its documentation.”

The documentation described the facilities. Group B read the documentation. Yet they lacked the theory—the understanding of when and why to apply those facilities.

What Naur Does Not Claim

Notice what Naur does not claim: he does not claim that all written communication fails to transmit theory.

Indeed, his own paper successfully transmits his theory to readers. Ryle’s The Concept of Mind transmitted his epistemology. Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions transmitted paradigm theory. Polanyi’s writings transmitted the concept of tacit knowledge itself.

A Crucial Distinction

This suggests a distinction:

| Documentation Type | Primary Content | Theory Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Technical/Artifact-focused | WHAT exists, HOW it works | Poor—assumes shared theory |

| Theory-focused | WHY decisions were made, WHEN patterns apply | Better—aims to build theory |

Technical documentation fails at theory transmission not because documentation is inherently limited but because it presupposes the theory it should transmit. It serves as a reminder for those who already possess the theory, not as education for those who don’t.

IV. Evidence from Cultural Transmission

If documentation in general could not transmit theory, human cultural progress through written works would be inexplicable.

The Renaissance

The revival of classical learning in 14th-16th century Europe depended on the transmission of Aristotelian and Platonic theory across a thousand-year gap via preserved texts.

Scholars who had never met an ancient Greek philosopher nonetheless acquired enough of their theory to extend and argue with it. The theory traveled through documents—imperfectly, requiring interpretation, but sufficiently to enable continuation.

Mathematics

Each generation of mathematicians builds on proofs and concepts transmitted through written works. Euclid’s Elements transmitted geometric theory for over two millennia.

The theory persists even when no living person possesses it through direct transmission. A student today can reconstruct Euclidean reasoning from the text alone.

Scientific Paradigms

Kuhn himself documented how scientific paradigms are transmitted through textbooks—written artifacts that somehow convey not just facts but ways of seeing problems.

A physics student learns not only equations but how to recognize when each equation applies. This is theory transmission through documentation.

The Question Refined

These examples prove that theory can be documented and transmitted. The question is why software documentation typically fails where philosophical, mathematical, and scientific writing sometimes succeeds.

The answer lies in what these successful documents contain: not just WHAT and HOW, but WHY and WHEN. They aim to build theory in the reader, not merely describe artifacts.

V. Why Technical Documentation Fails

Alistair Cockburn, commenting on Naur, suggests that technical documentation fails because it addresses the wrong target.

The Wrong Target

“Using Naur’s ideas, the designer’s job is not to pass along ‘the design’ but to pass along ‘the theories’ driving the design. The latter goal is more useful and more appropriate.”

Technical documentation describes artifacts. But artifacts are products of theory, not theory itself. Reading a program text tells you what decisions were made; it does not tell you:

- What considerations led to those decisions

- What alternatives were rejected and why

- What similarities the programmer perceived between this problem and others

The iceberg metaphor applies: documentation shows the tip (the artifact); the theory is the submerged mass that supports it.

A Reframed Goal

Cockburn further notes:

“Documentation cannot—and so need not—say everything. Its purpose is to help the next programmer build an accurate theory about the system.”

This reframes the goal. Documentation need not (and cannot) contain theory explicitly. It should provide sufficient material for a reader to reconstruct theory—to build their own understanding that, while not identical to the original programmer’s, is close enough to guide correct modifications.

What Experienced Designers Document

Experienced designers, Cockburn observes, often start documentation with:

- The metaphors

- Text describing the purpose of each major component

- Drawings of the major interactions between components

These are theory-transmission devices, not artifact descriptions. They help the reader build mental models, not just record facts.

VI. Forced Articulation

Having rejected the strawman (AI reduces labor costs, therefore solves documentation), we can ask what AI collaboration actually changes about Naur’s challenge.

The Interlocutor Effect

When a programmer works alone, much reasoning remains implicit. The programmer knows why a decision was made but never articulates it because there is no interlocutor.

AI collaboration introduces a persistent interlocutor. To direct an AI assistant effectively, the programmer must articulate:

- Intentions

- Constraints

- Rationales

- Criteria for success

This articulation is captured—in transcripts, in prompts, in session records—and becomes material for theory reconstruction.

Shifting the Boundary

This does not solve the tacit knowledge problem. Some knowledge remains beyond articulation—the Stradivarius problem persists.

But it shifts the boundary, making explicit what might otherwise have remained implicit. The interlocutor forces thoughts into words. Those words, once spoken, can be preserved.

The difference is not that AI extracts tacit knowledge (it cannot). The difference is that explaining to AI makes articulable knowledge actually articulated.

The Asymmetry

There is an asymmetry here that matters: the human retains theory between sessions; the AI forgets. This creates pressure to document not for the AI’s benefit but for the human’s future self—and for successors.

The AI is not the repository of theory. It is the occasion for articulating theory.

VII. Dialogue Preservation

Traditional documentation captures conclusions: “The system uses pattern X.”

It rarely captures the dialogue that led to that conclusion: “We considered patterns X, Y, and Z. Y was rejected because… Z was rejected because… X was chosen because…”

Reasoning Made Visible

Human-AI collaboration sessions, when preserved, capture this dialogue. The reasoning process—including false starts, corrections, and refinements—becomes available to future readers.

This is closer to how theory is transmitted in apprenticeship: not through manuals but through observed problem-solving. The apprentice watches the master think, not just act.

Historical Lineage

This insight has lineage. Nearly a decade before Naur, Kernighan and Plauger recognized that learning happens through concrete examples, not abstract principles:

“Good programming is not learned from generalities, but by seeing how significant programs can be made clean, easy to read, easy to maintain and modify, human-engineered, efficient, and reliable, by the application of common sense and good programming practices. Careful study and imitation of good programs leads to better writing.”

What K&P Couldn’t Preserve

Kernighan and Plauger could only preserve the finished artifact—the good program to be studied and imitated.

The reasoning that made it good, the alternatives considered and rejected, the false starts corrected—these were lost. The reader sees the destination but not the journey.

AI collaboration lets us preserve not just the program but the problem-solving process itself, fulfilling more completely what Kernighan and Plauger could only gesture toward.

VIII. What Remains Unsolved

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging what AI collaboration does not change.

Tacit Knowledge Remains Tacit

If a programmer cannot articulate why a solution “feels right,” AI cannot extract that knowledge. The Stradivarius problem persists. The Quality Without a Name remains unnamed.

AI can ask questions that prompt articulation. It cannot reach into the mind and pull out what resists words.

Judgment Cannot Be Automated

Knowing when to apply a pattern, when an exception is warranted, when apparent similarity is misleading—these remain human capacities that AI can support but not replace.

The AI can surface candidates: “This looks similar to pattern X.” Only the human can judge whether the similarity is deep or superficial, whether the pattern applies or misleads.

Theory Is Personal

Each programmer builds their own theory. Even with perfect documentation, new programmers must do the cognitive work of theory construction.

AI can provide more and better material for this construction but cannot perform it on the programmer’s behalf. Reading is not understanding. Being told is not knowing.

The Reader Must Meet the Writer

Theory-focused documentation still requires a reader willing and able to engage deeply.

If readers treat documentation as reference material to be consulted rather than as theory to be acquired, no amount of documentation quality will help. The transmission requires receptivity.

The best documentation is still only material for theory reconstruction. The reconstruction itself happens in minds, through effort, over time.

IX. Toward Theory-Resilient Documentation

If we take Naur seriously while acknowledging the genuine (if limited) changes AI enables, what practices follow?

Document Theory, Not Just Artifacts

Alongside (or instead of) specifications and API references, maintain documents that address:

- Why the system is structured as it is

- What alternatives were considered and rejected

- When patterns should and shouldn’t be applied

- How the system relates to the world it models

These are the questions a successor will ask. Answer them before they’re asked.

Preserve Dialogue

Treat AI collaboration transcripts as documentation artifacts. They capture reasoning in a form closer to apprenticeship observation than traditional documentation.

The transcript shows the problem-solving process: the wrong turns, the corrections, the gradual refinement of understanding. This is theory transmission material.

Embrace Redundancy

Theory is transmitted through multiple channels—prose, diagrams, examples, conversation. Redundancy is not waste; it provides multiple entry points for readers with different backgrounds and learning styles.

If one path is blocked (the reader doesn’t understand the diagram), others remain (the prose, the examples). Resilience comes from multiplicity.

Test Theory Transmission

The ultimate test of documentation is whether new team members can acquire sufficient theory to make correct modifications. This should be tested explicitly, not assumed.

Ask: can someone who has only the documentation modify this system correctly? If not, what’s missing?

Accept Imperfection

Documentation will never fully capture theory. The goal is not perfection but sufficiency—providing enough material that a motivated reader can construct a workable theory.

Some loss in transmission is inevitable. The goal is to minimize it, not eliminate it.

Conclusion

Naur’s pessimism about documentation is valid but narrower than often supposed.

What Naur Got Right

It applies specifically to technical documentation that describes artifacts while presupposing the theory needed to understand them.

Such documentation tells you WHAT and HOW but not WHY and WHEN. It serves those who already have the theory as a reminder. It fails those who need to acquire the theory as education.

What Naur Didn’t Foresee

Theory-focused documentation—the kind that has successfully transmitted philosophical, mathematical, and scientific understanding across generations—is not subject to the same critique.

Human-AI collaboration creates novel conditions that make theory transmission more likely:

- Forced articulation — The interlocutor makes implicit knowledge explicit

- Preserved dialogue — Reasoning is captured, not just conclusions

- Lower-friction iteration — Documentation can evolve with understanding

These don’t “solve” the documentation problem. They improve the odds.

The Challenge Remains

The challenge Naur identified remains: theory is built in minds, and documentation is at best material for theory reconstruction, not theory itself.

But with appropriate practices, we can create documentation that better supports this reconstruction—documentation that is theory-resilient in ways Naur could not have anticipated, even if it does not achieve the impossible goal of capturing theory completely.

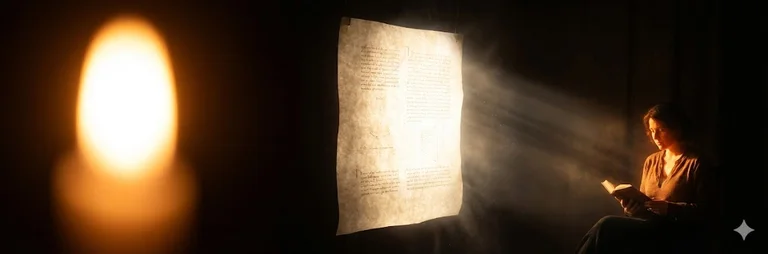

The Light Through the Document

The document is not the theory. It is a medium through which light passes—imperfectly, with loss, but sufficiently for illumination on the other side.

Our goal is not to trap light in paper but to make the paper translucent enough that light can pass through.

This document is living. It evolves with our practice.